Fighting Fake News

Proof and Probability

This post is also available in: German

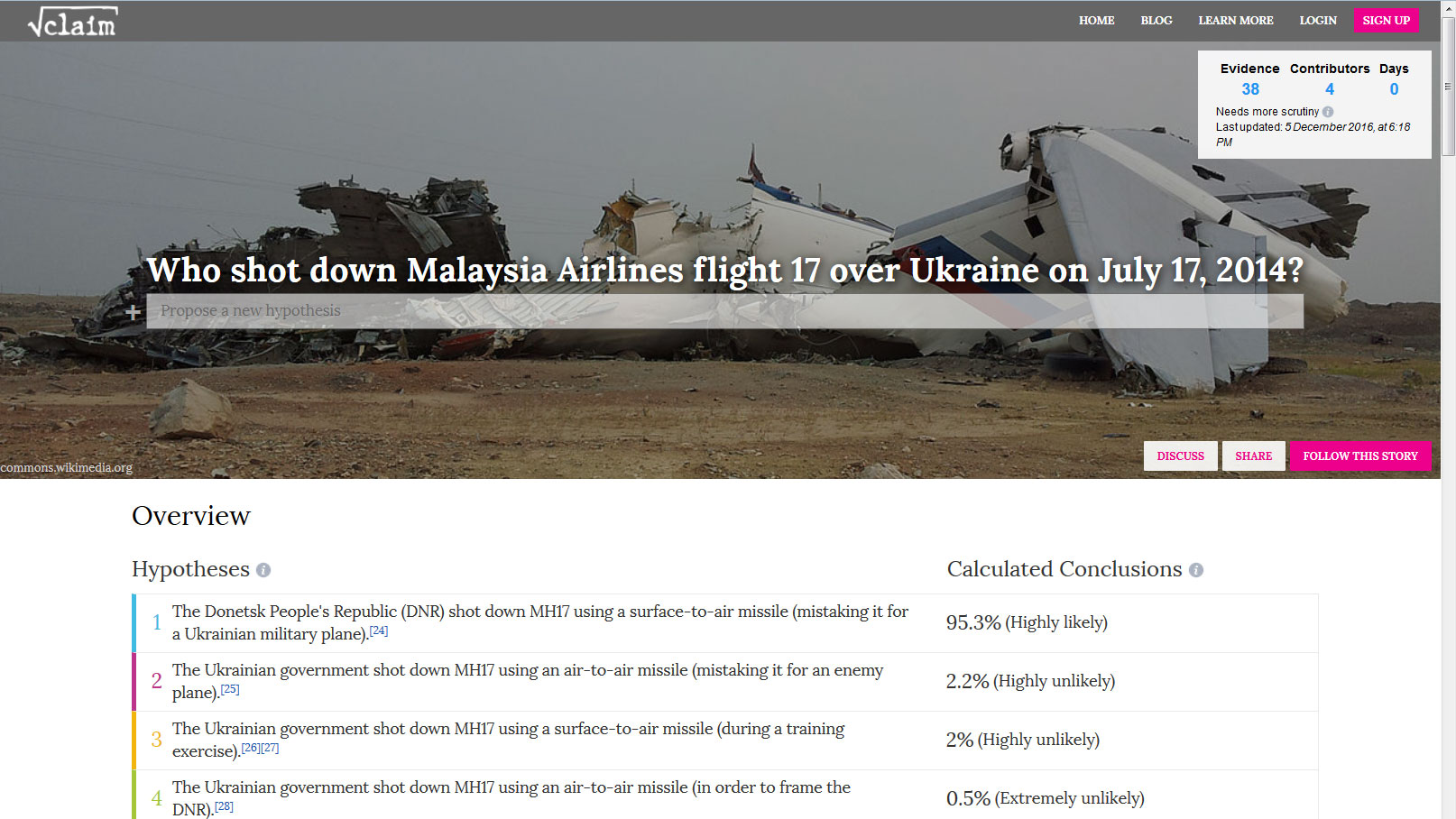

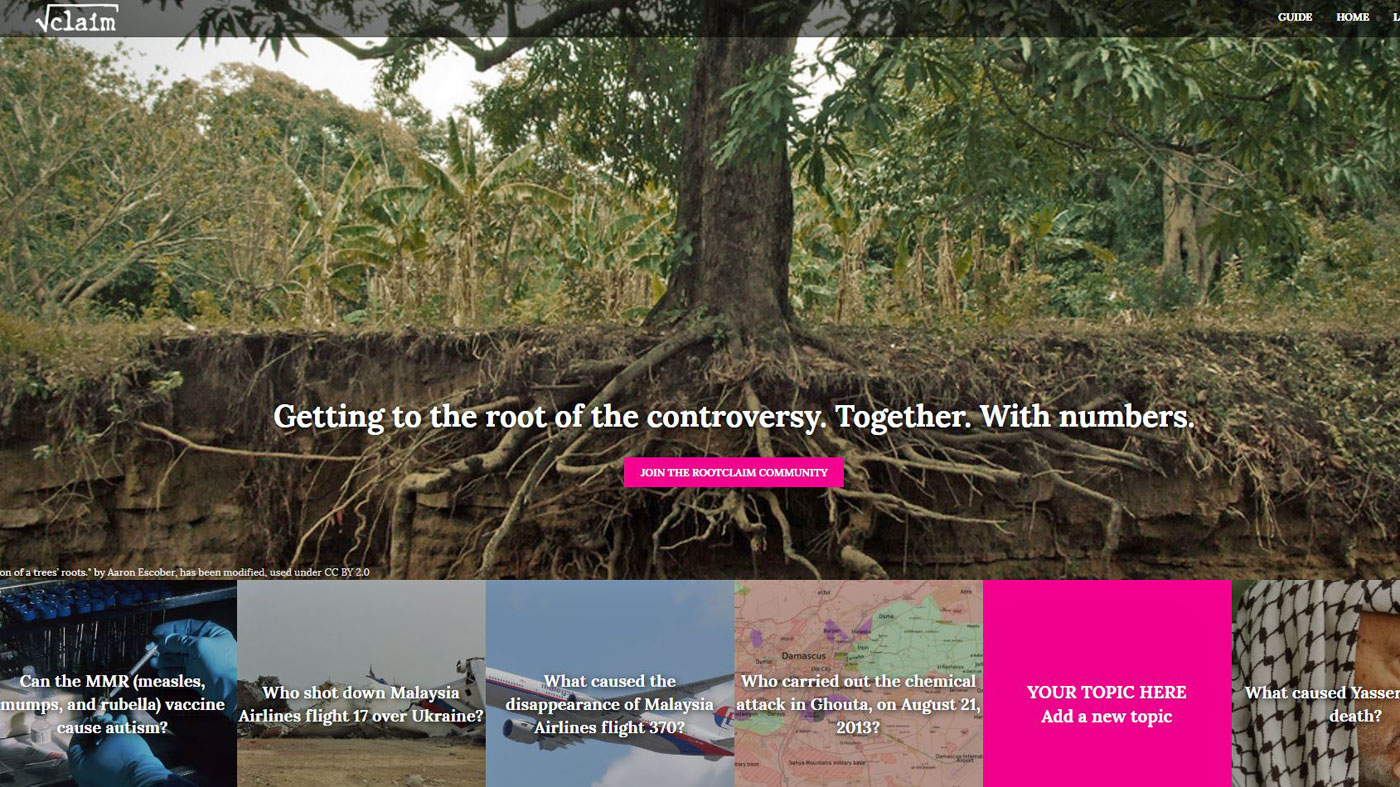

Was Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 really shot down by pro-Russian Militias? Who was behind the poison gas attacks in Syria? A startup from Israel worked out a methodology to help bringing the truth to light even from the murkiest of situations. Rootclaim’s approach is based on crowdsourcing and on the infallibility of mathematics.

An antidote for the post-truth era?

The truth is somewhere out there. The problem is: so are the lies. The internet and web 2.0 have challenged the media’s prerogative to explain the world. Legacy media outlets are being badmouthed as the “lying press”. Facebook is blamed for spreading fake news. Both in Europe and in the US demagogues and conspiracy theorists are on the rise.

Who can you trust?

A team of eight from Israel set out to bring the truth to light, or at least the most accurate betting line on current hypotheses. Rootclaim’s methodology is based on the concept of probabilities. In order to say what is likely (or in some cases extremely likely) the truth rootclaim relies on the crowd and on mathematics.

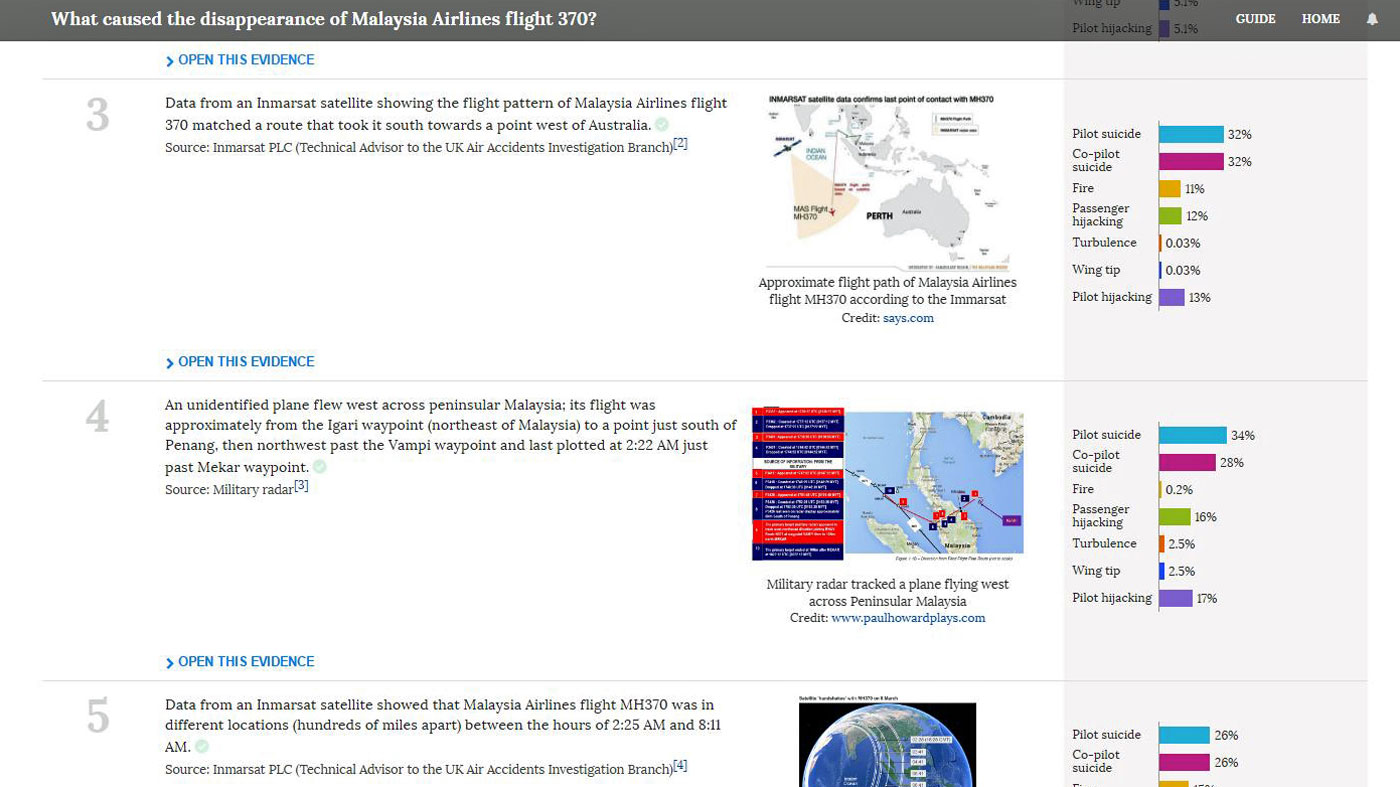

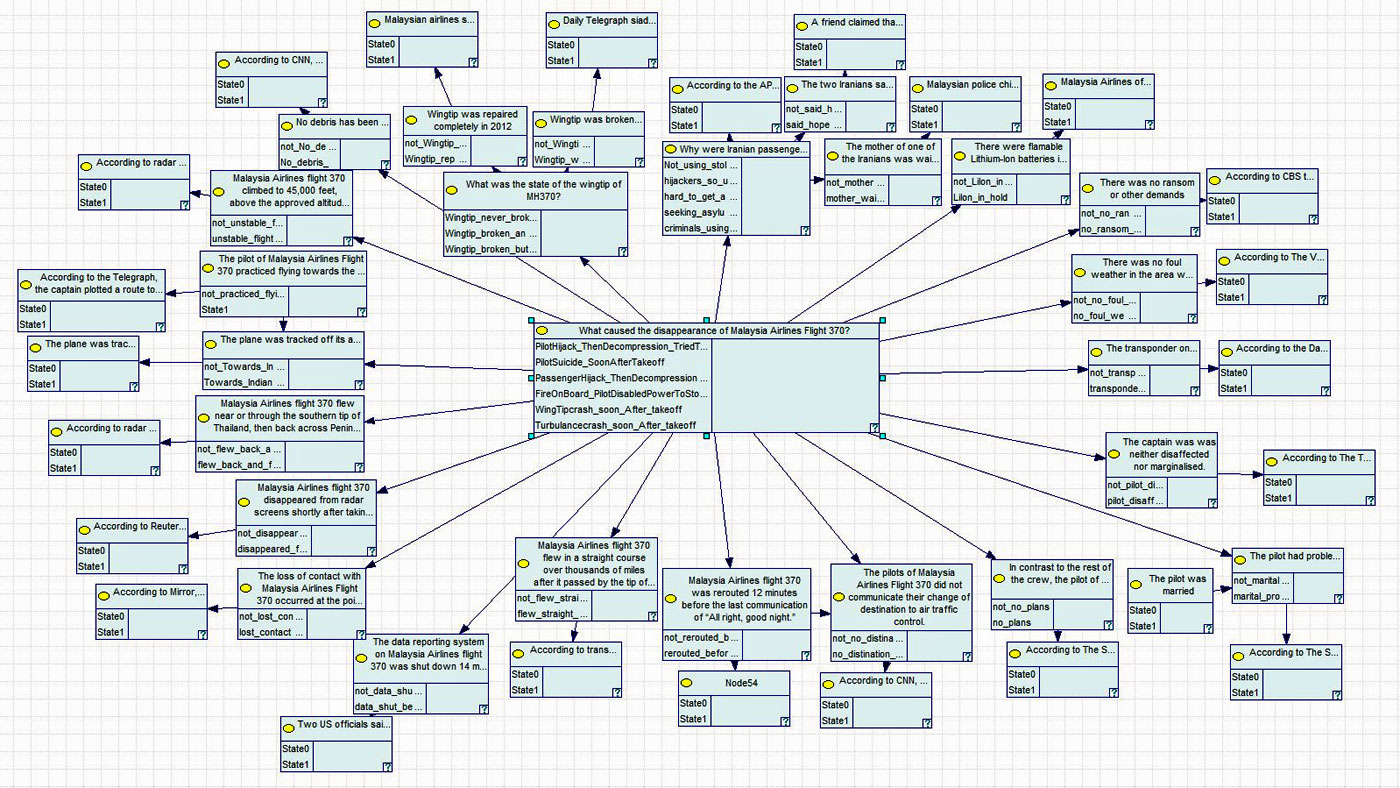

Visitors can discuss current topics on the site, or they can enter their own questions. Once entered, questions get divided up into subordinate, less complex hypotheses. Independent of the original question these statements will then be discussed publicly, and verified or falsified based on facts. There is no pre-conceived notion about the outcome — a similar procedure as in Wikipedia.

Can you trust yourself?

In order to get closer to the truth, rootclaim wants you to overcome your own worst enemy: yourself. Humans have an intuitive understanding of basic probability, but only up to a certain point. Studies find that people ignore or underestimate evidence that is inconsistent with their existing beliefs.

Furthermore, even before we add our own biases, the information available to us has already been heavily filtered and distorted. Readers can easily miss flaws in the arguments when they’re hidden in well-written, well-structured prose.

The platform integrates all available evidence, assesses it for credibility and uses probabilistic models to reach conclusions about the likelihood of competing hypotheses. Based on the accumulated facts hypothesisis can be checked for truthfulness by giving them a probability value. These values are then calculated with a mathematical formula (Bayesian methodology) and will come up with an answer to the original question.

Test your intuition in this video

Confirming and challenging mainstream media conclusions

In order to demonstrate the methodology the rootclaim team launches with seven case studies. The platform supports the conclusion, for instance, that MH17 must have been shot down by pro-Russian militias (with a probability of 95,3 %). In the case of the poison gas attacks the site comes to a different conclusion than the Western narrative. According to rootclaim the Sarin that was deployed in the Ghuta region came from Syrian rebel forces, not from Assad’s arsenals, as reported by many media outlets (probability 92,4 %).

The Interview

Last week I met with the two founders, Aviv Cohen and Saar Wilf* and the rootclaim team in Tel Aviv. It became a conversation about journalism, conspiracy theories and Donald Trump’s hair.

*Disclosure: Saar Wilf, is my brother-in-law

How it all began…

Saar, you’ve had the initial idea of Rootclaim for years. How did it start?

Saar: It was always clear to me that you could use rational thinking, math and data to better understand the world. It is strange that there are so many issues that we’ve been debating for sometimes even hundreds of years, like in economics, and there is no way to settle them. But it took me a long time to figure out something that works. Before Aviv, there had actually been three generations of the system that failed to produce consistently correct results. Well, each failure took us a step forward, and eventually we built something that really works. We developed a methodology of how to construct a Bayesian inference network that anyone can contribute to, and is completely open to scrutiny.

So this is the fourth attempt. What went wrong before?

Saar: Initially it was more focused on logic. It took me way too long to realize that logic is something that doesn’t have any applicability in the real world. Logic is how people normally think about the world, but it only works when you can get absolute certainty on the inputs, and that’s just not possible in real life. When you use logic, this uncertainty accumulates the more information you add until eventually you reach meaningless conclusions. Each generation of the system integrated more concepts from probability, and when Aviv came he convinced me to shift to a fully probabilistic model.

The old models were pretty easy to manipulate into wrong conclusions. The current model is very structured and robust. It is mathematically proven to be correct, so it can fail only when the inputs are incorrect. If someone doesn’t agree with its conclusions then he needs to prove that one of the input numbers is incorrect or that evidence is missing. To make sure the inputs are correct, they are completely open to scrutiny. Anyone can add evidence, anyone can contest any number. The crowd can always improve, can always check everything. It’s like an open-source software — since it is constantly checked by thousands of developers you can be pretty sure there is no malware inside, for example.

Who else is working in your team?

Aviv: The folks on our team wear a few hats. The first hat is to research the stories we analyze. Since we hadn’t had the crowd before the site was launched they had to simulate the crowd. This means that they were looking for evidence online, information that was important to the case at hand. They researched the input probabilities of certain evidence being true. On top of that we developed the user interface together — that was a team effort. The Bayes network software existed long before us, but the methodology of how we take complex situations from the real world and model it to the network did not. We had to come up with all kinds of rules and guidelines that helped us through this process. The team learned and developed it all together.

They are not journalists?

Aviv: No, they are not journalists. They don’t investigate and they don’t report. They don’t call up sources and try to get new information. All they look for is publicly available evidence. Stuff that has been published in newspapers, on the web, on TV, or even by individuals. We’re not in the business of uncovering new information that a secret source may give us. Rather, our focus is on better analyzing and putting together all the different pieces of information that already exist and coming up with a mathematically sound conclusion as to what is likely to be right. One of our discoveries is that often the solution is already available in publicly available evidence — we just can’t “see” it, because of the limitations of the human brain.

What exactly can the machine do better than the human brain?

Saar: People usually take a big complex question with many different pieces of evidence and try to answer the question based on the entire evidence body at once. This is a very difficult task that is beyond the capabilities of the human brain. We stumble in all kinds of cognitive flaws and biases when we try to do that. .

Aviv: What our methodology does is allow us to turn things around. Instead of asking: Given all the evidence which answer is true? We turn the question around and ask “Here is one piece of evidence, how often do you expect to encounter it if answer X was true?”. For example, we had a case of a person who had been found dead and the question was whether he had been murdered or if he had committed suicide. There were over sixty pieces of evidence. So we look at each piece of evidence “in reverse”: How likely it is given each hypothesis.

In our example, one of the pieces of evidence was that there had been no gunpowder residue on his hand. So given that our man had shot himself, what is the probability that there was no gunpowder residue on his hand? Remember: This was only one of about sixty pieces of evidence. Imagine the amount of evidence and probabilities all together — you get lost. When you turn things around and break them down the questions become relatively simple, straightforward and also less prone to bias.

This is something people can do, for example by bringing statistics from similar events in the past. We get all these answers and the algorithm takes all of them as inputs, calculates them altogether and outputs a conclusion that is an indisputable mathematical result. If the conclusion doesn’t seem right to you, you can challenge the inputs. But once we agree on the inputs the conclusions are indisputable. That’s math. It’s based on Bayes’ theorem. It’s like 2+2 equals 4.

How do you prevent conspiracy theorists from taking over your platform?

Aviv: First of all, we don’t necessarily want to prevent them from using our platform. If they can provide evidence, who knows, their conspiracy theory may be true. Everybody is welcome to contribute evidence. If somebody claims, 9/11, for example, was perpetrated by the US government, fine, contribute the evidence, maybe you are right. We are not biased. In fact, we did find a couple of claims, that some would call “conspiracy theories”, to actually probably be true.

A problem with some conspiracy theories is that people give all kinds of possibly plausible explanations to individual pieces of evidence but then the whole story doesn’t hold water together. Your explanation of evidence number one may make sense and your explanation of evidence number two may also be reasonable but the two explanations are contradictory — they are unlikely to be true at the same time. It is difficult to detect these things, whereas with a system like ours contradictions like that surface immediately.

The more information there is, the better your results. Is there a minimum set of data required to be certain that your conclusion is correct?

Saar: Since our framework is probabilistic, we can measure this uncertainty. So when you have little data, the conclusions would have high uncertainty, for example 65%-35% for two hypotheses. As more information is added, it will converge to say 99%-1%. Once you’re there, you’re not likely to see this balance flip back, since that would require very strong evidence to come up, and by definition strong evidence is not likely to appear for the wrong hypothesis.

Aviv: Even when there’s little evidence going around, there is still great value in knowing what is most likely to be true. Sometimes that’s the real world. Imagine a new situation developing as we speak, nobody knows exactly what has happened, but there are a few initial reports — We can still say that based on this data, it’s more likely that A has happened than B.

Saar: When new stories develop, biases, prejudices and conventional wisdoms dictate what people think is going on. People tend to jump to conclusions. We provide information from all the available data, calculating all sides of the story. As we grow, we will rely on the crowd to supply this information. What we hope is that people with very strong feelings on all sides of an issue will contribute, even if only to “their” side.

Rootclaim’s analyses are a product of collective work and take time to mature. Is that relevant in a world where everyone expects instant results?

Aviv: We’re not in the business of simple fact-checking, where the right answers are easily verified. We take on very complex controversial questions, where there are several serious contenders to the “right answer”. Addressing all the evidence and details of these issues requires research and we rely on the horsepower of the crowd to get it done. As more work is put in, the accuracy of Rootclaim’s conclusions improves. As more people are engaged, conclusions can be reached in days or even hours. Don’t forget that today these issues can easily remain unresolved for years.

You’re about to launch your platform with a set of stories: What happened to the missing Malaysian airplane? Who was behind the chemical attack in Damascus? What’s the truth about Trump’s hair? Why did you choose these kind of stories?

Saar: First, we look for stories that are interesting to a global audience. Then, we look for stories where the answer is unsettled. That’s where our system shines. If we’re lucky, we find a story where the most likely answer is not what everybody thinks or the media reports. In other words, we look for interesting stories where there is no clear answer, and the reason why there is no clear answer is because there is evidence in every direction.

Where does your platform reach its limits?

Aviv: There are types of questions we put on the back burner for now, because they have some characteristics we haven’t focused on yet. We know how to handle them conceptually but we have not yet implemented the methodology to deal with them. Rootclaim now supports questions that consider a few discrete hypotheses that revolve around concluded outcomes. In the future, we will go into complex models involving continuous answers, forecasting and decision-making, like “Is climate change real and what should be done about it?”. But answering these questions all rely on the same mathematical fundamentals. It is more complex but not conceptually different. There’s nothing preventing us from moving in that direction.

How do you want to make money with Rootclaim?

Saar: Well, currently we’re just focused on making sure the site is launched properly, the crowd engages and everything runs smoothly. We hope that we can have a positive impact on society, people’s understanding of issues and decision making. We have a few ideas for the future. Perhaps implement our system in organizations — public or private — that want to analyze complex questions internally. Their crowd would be their employees or internal experts. Together they can analyze rationally what are the best decisions or insights for their needs.

You both have worked together at Fraud Sciences. Are there similarities between credit card fraud and lies that we are confronted with in the news?

Saar: The fundamental idea is similar. When it comes to online credit card transactions, there are only two options: either you have a legitimate buyer or you have a fraudster. Then you have all sorts of evidence — sometimes evidence only we were aware of: how the buyer connects to the internet, what kind of e-mail address he uses, etc. Instead of looking directly at all the evidence and jump to a conclusion, we turn the process around and say: If he were a fraudster, how likely is it that he would be connecting from behind a proxy server? And if he were a legitimate person, how likely would that be? So what Fraud Sciences did was ask all these questions for many indicative parameters that helped us distinguish between fraudsters and legitimate buyers. This Bayesian approach was not invented by us. It is used in many fields: transportation, medicine, communications. We are the first ones who are making it easily accessible to the public, to tackle questions in any field. Mathematicians often shy away from such questions.

But what if the input is wrong or not sufficient enough?

Aviv: Certainly, our analyses are not perfect but we use the best approach available to deal with uncertainty. We jokingly say that we are a little bit like democracy — the worst analysis method except for all the other methods. When you read an article about, say, the missing Malaysian airplane, and you have a hard time making sense of it, we tell you, based on all of the available data, with an explicit probability that this is what has most likely happened. That gives you at least an idea of what the truth may be.

Aren’t estimates like that a little bit risky? We all remember what happened with the predictions around the US presidential elections.

Aviv: Definitely. And Rootclaim conclusions will also come out wrong. Our goal is to reduce uncertainty as much as possible — eliminating it is impossible. The system is designed so that if we conducted a 100 analyses that each gave its leading hypothesis 90%, then only 90 of those should turn out to be true. If all 100 turn out to be right then the system actually did a bad job! It means it was too “careful”.

With systems like yours, do you think one day computers will become the judges even in courts of justice?

Aviv: Judges are people, even if they are educated and experienced people, and therefore fall in the same cognitive pitfalls we mentioned. I’m sure that having probabilistic systems in the courtroom could help judges a lot. In our research, we looked at several court cases and in some of them judges and juries have misinterpreted probabilities very poorly. You can look at the Innocence Project in the US, where more than 300 people were exonerated using DNA technology. We feel this could revolutionize the judicial system, but we’re not very optimistic this is going to happen any time soon. The judicial systems we know are centuries old…

Do you think Rootclaim could help bring back trust in the media?

Saar: Not sure. Today there are many media sources — TV, blogs, social. People tend to go to the outlets they agree with anyway. Thousands of scientists may say one thing and one guy in his garage says the opposite on his blog. So whose word do you take? We can take all the evidence, consider its reliability, put it to the probabilistic test and come up with the most likely conclusion. That’s what we can help with, but it probably won’t stop anyone from publishing nonsense.

How do you convince people with facts in a post-truth society?

Aviv: There seem to be many people out there who don’t let the facts confuse their opinions. Rootclaim is for people who care about reality and facts. However, people may sometimes have “context-based rationality”… If you are clearly and emotionally on one side of an issue, I don’t think we will convince you otherwise, but we can help you with other issues. For instance, take a young mother. Her baby is scheduled to get vaccinated and she reads on the web that vaccines cause autism. She hasn’t investigated this but she does care, because it is her baby. We may give her more confidence about her choice, even if her best friend has told her otherwise. So I think, ultimately our site has some value for everyone. Irrational people have babies, too.

Aviv Cohen – Among other leadership positions, Aviv ran the business side at Fraud Sciences (acquired by PayPal/eBay), which revolutionized online fraud detection using advanced probabilistic models. Aviv earned degrees in Statistics, Computer Science and Management from MIT and Tel Aviv University.

Aviv Cohen – Among other leadership positions, Aviv ran the business side at Fraud Sciences (acquired by PayPal/eBay), which revolutionized online fraud detection using advanced probabilistic models. Aviv earned degrees in Statistics, Computer Science and Management from MIT and Tel Aviv University.

Saar Wilf – A serial entrepreneur since 1997, he founded several technology ventures, including Fraud Sciences (acquired by PayPal/eBay), Trivnet (acquired by Gemalto), and ClarityRay (acquired by Yahoo). He is currently co-founder and chairman of several technology startups, including Pointgrab, Deep Optics, and Rootclaim.